Sunday, January 30, 2005

"Poetry is what is lost in translation."

So said Robert Frost.

If my writings were even just a little poetic, then I could say that must be what's wrong with Google's translations of them. Take a look at Google's Spanish translation of my previous entry. I'm amused, for example, that "the Book of Job" is translated "el libro del trabajo", or "the book of work". Since "Job" with a long O sound is stored in a completely different place in my brain from the word "job" with a short O, I actually spent a moment of dissonance figuring out why the automated translator had chosen the latter.

(My Francophile friends may enjoy opening google.com/fr, typing in " link:blog.renice.com", or another favorite URL, and clicking "Traduire cette page".)

I'd found the Spanish translation only because I noticed in my logs that someone in Spain is reading translated versions of these entries. Since the translations don't always make sense, I'm wondering what conclusions my Spanish audience has reached. I'm also wondering if these translations don't, to some extent, offer a new way to think about accessibility. At any rate, I'm having some fun reading the translations.

I love Spanish. I took 3 years of Spanish in college, even though it meant I had to petition the dean to count the language toward my Art History degree (French, German, or Italian were preferred). Although I've never been able to roll Spanish off my tongue as fast as a college friend, a certain amiga Puertorriqueña, chided me that I should, I have always loved hearing and reading it. Back as an undergrad, I had planned to live some day in a Spanish-speaking country – in fact, I hope to yet.

Of course, some may argue that I live in a Spanish-speaking country now – and I have to admit that I've had occasion to agree.

[Next: How I became La Secretaria de la Línea.]

Tuesday, January 11, 2005

Of Biblical Proportions

A frightening video of tsunami waters surging through Banda Aceh was aired on NBC News last night. It's also available on video.msn.com (thanks KB), for Win users ( only – Bill strikes again). The images give a whole new meaning to the word debris – "bits and pieces left from destruction" * hardly fits. In the video, you scarcely see the violent waters – it looks more like a grey glacier of garbage rushing down a steep grade, except that the weather is tropical and the street is flat.

Once again, the undercurrents of my father's traumatic childhood resurface in my limited little brain. Because his family had drowned, my father was adamant that his kids learn to swim. Trying to quell his anxieties, I worked hard to succeed in the classes he sent us to. At 10 and 11, I rapidly ascended skill levels so that I was swimming with much older kids (competitive military brats, all). With each of my promotions, my father's pride swelled. He even bragged that I would compete on the Olympics swim team some day. Unfortunately, I deeply disappointed him a few years later when I stopped swimming (I'd become conscious of not fitting the prevalent Texan tastes in women's body types and avoided swimsuits throughout my teens).

While watching the Banda Aceh video, my father's obsessive push for us to swim suddenly didn't make sense to me. His family didn't drown because they couldn't swim. Newspaper accounts quote witnesses telling how his father, Clarence Wernette (usually misspelled in the reportage), heroically rode his horse through the current to rescue neighbors who'd built their homes closer to the river – and how he was hit by a tree limb and slipped unconsciously under the muddy torrent. His wife and two daughters, whom he'd left 'safely' on higher ground, were killed a bit later by a crush of water and the debris of the house he'd built for them.

Since December 26th, I've read dozens (hundreds?) of stories and commentaries on private and commercial news websites from around the world. Over and over I've read of people ascribing that day's natural disaster, or surviving it, to either the grace or the vengefulness of gods of various belief systems. In response, I've been devising an entry on why the Book of Job has been my favorite since I'd read the Bible over 25 years ago – how, since the 1980s, I've responded to misguided Christian friends who insisted that disease, especially AIDS, was divine retribution with, "Really? Have you read the Book of Job lately?"

But in his NY Times op-ed piece " Where Was God?", William Safire makes my case far better than I could have. Overall, he nails it. Certainly, as Safire writes, one of the lessons from Job is that "suffering is not evidence of sin." And, although I'd never looked at it this way, I also like Safire's argument that "questioning God's inscrutable ways... need not undermine faith." However, Safire and I may diverge slightly on the lesson to take from God's response to Job's defiant questions. I've always thought the concluding point was not that we creatures, with our limited little brains, can safely question God, but rather that... there is simply no point.

Wednesday, January 05, 2005

More Blogging on Blogging

Over the last 3 days, I've read a number of articles in the commercial media on the 'phenomenal' influence of blogs this year. I've gotten the strong sense that, when people in commercial media say "blog", they're actually saying, "An Unexpected Goldmine of Ideas and Developments Delivered Directly from the Hoi Polloi", rather than the more tactful definitions for "blog" that they routinely provide their technophobic readers.

After reading several commercial media references to the blogosphere's "echo chamber effect" (which is a popular topic among bloggers as well, e.g., Kevin Werbach, David Weinberger, Joi Ito), I went searching for perspectives contrary to mine. Using Technorati's blog-search engine, I used the keywords tsunami and catastrophe to see what others are thinking about The Big Story. In this eye-opening random tour, I read: - an assertion that an effort to rescue tsunami-dazed dolphins demonstrates the Wildlife Friends of Thailand's poor priorities*

- a lament from various right-wingers that the US should not provide aid to any country that harbors people wearing t-shirts bearing Osama Bin Laden's image*

- a comment from an Australian in SE Asia who mentions in an aside that everyone in the region noticed how much longer it took American forces to arrive *

- complaints that westerners need a "a blond haired, blue eyed kid to bring home the death of tens of thousands of brown babies"*

I also found a tiny bit of what might be evidence of the "self-healing" aspect of blogs (as mentioned in commercial media articles) from updated posts like Corey Koberg's, warning that all the scary images bandied about on blogs, including his before someone set him straight, may not actually be images from The Super Tsunami.

All in all, I'm not sure what to think now, except that, while I love the Unexpected Goldmine of Ideas and Developments Delivered Directly from the Hoi Polloi, I still want to read the commercial media – as long as they're not seduced by the immediacy of blogs, but strive to deliver well-sleuthed and professionally edited journalism.

ADDENDUM – 12:33 PM

While I was writing the entry above, I was reminded of an article I'd read in the Smithsonian magazine during my wait for a doctor yesterday. I couldn't remember which issue I was reading, but, thanks to a quick and helpful response from Carolyn McGhee of Smithsonian Reader Services, I've found the article on their thorough website. See " All the News That's Fit to Sing" from the October 2004 issue for an interesting history of journalism and the early reliance on rumors and gossip – seems bloggers have established a new globalized "Tree of Cracow".

Tuesday, January 04, 2005

Mystic Mischief

My father's childhood trauma had other odd repercussions. One thrust on me when I was 8 or 9 was the idea that his survival had been an act of divine intervention. My mother's cousin and her 3 kids explained with some satisfaction, that my father had been saved because he was meant for great things.

The idea was quite staggering to me, and my cousins pressed the issue as confusion certainly spread across my freckled face. The 3 kids, all within 2 years of my age, and their mother explored with infectious enthusiasm all the 'great things' that could be my father's 'destiny' – perhaps he would save others, perhaps he would be an important leader, perhaps he would discover something valuable. "Or perhaps," said my mother's cousin, "he was saved because Renice or Chris is meant to do something important." With that, her 3 children turned widened eyes to scrutinize my sister and me.

Suddenly I understood how weighty expectation is. In that instant, I saw a new dimension of my father's struggle with depression. Only years later would I learn the term " survivor guilt" and know that it is far more complex than a mere sense of unworthiness.

Yesterday, as I read the NY Times article " Myths Run Wild in Blog Tsunami Debate", I was reminded of the deep need to explain what we can't understand by using the supernatural.

The article recounts how a participant tries to bring rationality to a lively discussion on explanations for the tsunami devastation: "Not to make fun, as I'm sure it's not a unique misconception ... but the reality is simple plate tectonics....That's it. No mystic injury to the Gaia spirit or anything."

A very similar debate between mysticism and logic has raged in my own head since the day my cousins turned anticipation-clouded eyes in my direction.

Monday, January 03, 2005

Undesirable Baggage

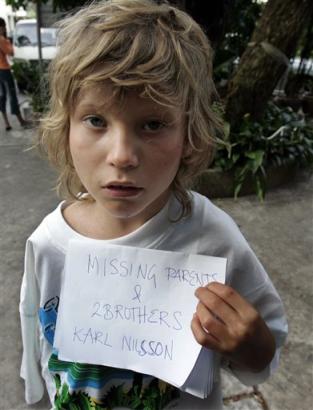

My father's childhood trauma affected him, and his kids in turn, in odd ways. Unlike little Karl Nilsson, of whom I wrote in the previous entry, my father survived his family by "conning" (his word) his sister out of her turn to visit their grandparents a few days before the flood.

Even while I was a small child, I recognized his conflicting feelings about traveling. He yearned to travel, but once at the destination, he became impatient and fidgety. Our family vacations were tense and most often cut short – I always felt that he worried our house would be gone if we didn't hurry home.

Now, even though I try to be conscious of how his behaviors, and all the fears they conveyed, affect me still, I sometimes forget the roots of my vague anxieties over thunderstorms and travel. For decades now, I've had to work to quell impulses to rush home and call everyone I love whenever the skies darken suddenly. And I still have to remind myself not to constrict my lungs while a loved one is in flight. Brad and Jolie are remarkably sympathetic when these irrational anxieties surge.

Before dawn this morning, we saw Jolie off at the ever-frustrating Willard Airport – one Homeland Security suitcase-check person for 7 ticketing agents from 2 airlines. Geez. An hour after arriving at the airport the final boarding call was announced, and Jol was still queued for the carry-on scan. Once through, she had to run for the gate. And I went home to hold my breath until her call. Five hours later she called from her place, and my peculiar uneasiness was relieved once again.

Sunday, January 02, 2005

Selective Perceptions

Travis has me thinking about a few things. For one thing, I'm reminded of how much I value other perspectives – we tiny creatures are utterly isolated without our conversations, sometimes without even recognizing how isolated. Travis's post of the image that helped him understand what's happened in Southeast Asia reminded me of one of my foibles which I only first recognized while a grad student. Rob and I had met for our semi-weekly lunch at Intermezzo Café. Throughout the hour, while we sat next to the floor-to-ceiling windows, I often gazed at the pattern of snow melting off the small river rocks spread out beside our feet. Before we left, I thought I should share with Rob how beautiful the image was that had captivated me throughout our discussions. He agreed it was beautiful and laughed hard because he hadn't noticed it previously. Then he said he'd reciprocate by pointing out all the dead birds he'd been counting during the same time. (A few years later, I tried to convince Krannert Center authorities to post hawk silhouettes to curb the carnage, but their sense of aesthetics prevailed. Years after that, I knew exactly where to go when I wanted a dead bird for one of my pieces.) As Rob pointed out one lifeless songbird after another resting on the grey pebbled terrace, I was stunned: I had looked directly at them, but hadn't seen one. All these years later, my perceptions are just as selective as ever; I couldn't see the bodies in the image that had so strongly affected Travis until he pointed them out. And I am once again taken aback.  Travis also pointed me to this heartbreaking photo of 7-year-old Karl Nilsson, the only surviving member of a family of 5. It reminds me of another of my endless foibles: My understanding of others' experiences is limited by how they relate to things from my own life. In this instance, I'm reminded of a yellowed newspaper's front-page photo my father showed us while telling us about his childhood. The old news photo depicted a little blond boy looking numb and lost as he was lead down courtroom steps by 2 towering officials. (As the only surviving member of a family of 5, my father was further traumatized when 3 different families battled in court for his custody.) In a recent article, a woman now caring for Karl "Kalle" Nilsson said, "All night, when he heard the noise of a truck or car, Kalle woke up and asked me, 'Is it another wave coming?'" Even this saddens me by resurrecting my own images of my father nervously pacing and chain smoking during heavy rainstorms to this day. The word history connotes wide sweeping panoramas of the whole past of humanity, but in these tiny paralleled stories of 2 little boys separated by half the globe and three-quarters of a century, history repeats in miniscule ebbs and swells. Nature's most recent reminder of what tiny creatures we are on this earth has lines from Shakespeare's 60th sonnet reverberating across my sad and sadly fading synapses: Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore

So do our minutes hasten to their end;

. . .

And nothing stands but for his scythe to mow.

. . .

Saturday, January 01, 2005

Of Words and Images

A co-worker posted a link to an extraodinary series of photos taken from a Phuket hotel balcony. Although the man was pulled out seconds later, I find this image especially chilling. Nevertheless, a statement only tangentially related to the catastrophe in Southeast Asia hit me with more visceral punch than any image thus far.

The History Channel had an old series on natural disasters, and a couple of nights ago they replayed " Tsunami: Killer Wave". In the episode, they talked about how hard it was, in spite of an early warning system in the Pacific, to convince people of the danger. Apparently, during one such warning in Hawaii, surfers wouldn't come in – they couldn't be convinced that this particular wave wouldn't be an awesome ride. But, as one scientist explained, a tsunami wave is under the surface, unlike the typical ocean waves we're used to. He said a tsunami acts more like flood waters.

For someone raised by a traumatized survivor of a river flood who couldn't instill in his kids enough fear of floods, that was a body slam.

|